So what about you? Would you participate in the slap? What if it was with your friends? What if it was with strangers? Why? What would make the difference?

I’ve been crying a lot recently. From anything. And…pretty much everything. Not always out of sadness, but instead a lot of it is stemming from sentimentality. Music. Particular songs. Seeing my car back in my garage after months in the shop. New cushions for my outdoor chairs. Being outside. Memories. Night. Morning. Mourning. Dancing. Little Notes. Jokes. My desk. Compliments. Listening to the Hook Soundtrack. Watching my kids play quietly. Watching my kids not play quietly. My plants. Walking around my house. The house being clean.

All of it can and has made me cry.

I feel like I have a lot I’ve been racing to get back to. And then revisiting old messages, I’ve been reminded that there is no going back. And forward is a mystery. I had someone close to me ask me recently why I feel I’ve got to keep running forward and reaching for that “unreachable star.” I said it’s just felt like a core aspect of my being. Between the German concept of “Sehnsucht,” (an intense yearning for something far-off and indefinable) and the British concept of “Coddiwompling,” (traveling purposefully toward an as-yet unknown and vague destination) I keep running forward.

My friend said this was interesting because it means I’ll never feel settled or just be.

I’ve thought about that a lot since, and I think that I used to chase this unknown hoping that I’ll know it when I reach it, and when I do, it’ll help me feel settled, and I’ll be able to just be. Because I’ve found and know what I’m chasing. I’ll have reached my unknown destination.

I don’t know what I want anymore. I don’t know what I desire.

I never did.

But I got pretty good at convincing myself that I knew. The thing is, all that running forward, reaching for the unreachable, chasing the unknown, left me unable to appreciate what I had until after I ran too far away from it. “Don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you got til it’s gone…” And yet here I am, facing the fact that I thought I found what I’ve been chasing, and fighting to make sure I don’t lose it, all while feeling the pull that it’s time to start running forward again.

(I’m crying again, but this time out of…contemplative gratitude.)

And so I’m facing a new kind of hurt. A new kind of suffering.

At a recent Philosophy Club meetup, the main question posited was, “Why do people hurt people?” And the classic philosophical fashion, it was left intentionally open ended to allow it to spin into whatever direction and discussion it went.

Ethics and morality were brought up and discussed.

Intentionality as well.

And consent.

But then also inevitability. As if pain and suffering were inherent to living, and particularly the human condition.

And then a discussion on forgiveness…

Which then pivoted into the debate between determinism and free-will.

Which ultimately led back to ethics and a question of what should we do? Do we strive to minimize hurt? But hurt is a part of growth.

Hurt can be good.

And then the conversation all kind of congealed and all the previous points faded in and out and I don’t remember much else save for the fact that while I was so excited to be back in deep meaningful discussion, it made me miss my big classroom whiteboard. That, and the fact that while it was a great discussion, I just had this feeling that it was more about people airing their grievances in a manner and forum that allows to seemingly discuss them without directly addressing them personally. To broach the personal hurt in a generalized and impersonal manner.

I didn’t think I had anymore to say or to add after the meetup ended, but as is often the case with me, I don’t have my full thoughts on a matter until I haven’t been thinking about it for a while and realize I’ve been thinking about it the whole time.

Why do people hurt people?

Because FEAR! People are afraid. Sure, I don’t disagree. But while that may seem like the core answer, I think there’s more to it. It’s a little too straightforward and rudimentary

One of the classic statements brought up was, “Hurt people hurt people.”

But again, part of the discussion was the inevitability and inherent human condition. We’re all hurt people. So hurt people hurt hurt people. Or maybe its better understood to say hurting people hurt other hurting people* (with the addendum that hurting people include themselves: hurting people hurt themselves,and hurt other hurting people).

This is where I began to spin out a little bit. For one, hurting and hurt then became two different concepts. If we’re all hurting, then it’s not the same as to be hurt. Which means maybe the hurting is the bit that is inevitable and inherent to the human condition, and the hurt is conditional and circumstantial.

And while I do believe the two concepts correlate and are connected, the more I mulled over it, the more I came to two questions:

What is hurt?

What is hurting?

PART 1:

WHAT IS HURT?

Well on the most rudimentary level, to be hurt is to experience pain.

Pain is an alarm system, of sorts. It indicates damage to our bodies and exists for the purpose of survival. It signals something to avoid, danger. Unwanted harm (damage) or potential harm (damage) that is a threat to our survival.

(Psychological/emotional pain is similar, but applied to social dynamics.)

But people hurt themselves all the time. Getting a tattoo hurts. Working out hurts. Learning a new thing hurts. Growth hurts. That’s why they’re called growing pains. But those are good hurts. Good pain. So I suppose I should clarify that I don’t mean any pain that we’ve weighed as a process to something greater. Or rather, that we’ve determined that the pain is good and desirable. That cannot and will not be what I mean by pain.

At least for now.

I’m fully confident that quite a few people watching the video up at the top suddenly realized they had a slap kink they never knew about before. Or at least a lot of people wanted to participate in it.* (*EDIT: yes, I KNOW about the Max Landis allegations)

I showed that video to two friends and we actually then went through with full on slapping each other. And it was one of the most…experiences I have had in my life.

But we wanted to.

I wanted to.

And WHY?!?! If I wanted to be hurt, then it isn’t really hurting me. Because I desired something, and I’m getting what I desired. So I’m clarifying right now:

There exists instinctual pain that our bodies and human makeup are wired to avoid in order for our survival. Flinching, fight flight or fawn, inherent neurological and physical nervous system responses that occur without or choice. These responses can be overcome when we desire something that triggers these instinctual primal responses. For example: the thought of performing an open mic triggers fight or flight in you, but you do it anyway. And you’re uncomfortable. So you actively choose to resist your instinctual responses because you want to.

Pain is only pain when we’re aware of the danger of harm it poses to us, and we actively and consciously both desire to avoid it, and act to do so.

Put simply, I’m saying here that pain is only pain that is consciously and actively unwanted.

So what is hurt?

To be hurt is to experience pain in a way that you do not desire.

This re-frames the original question posed, why do people hurt people, as:

Why do people cause others to experience undesired pain?

Sure, now you can get into a discussion of intentionality (Are they doing so intentionally or unintentionally?) psychology, psychoanalysis, and therapy (are they victims themselves, childhood trauma, insecurities, etc).

But for me, I’m going to the next question:

PART 2:

WHAT IS HURTING?

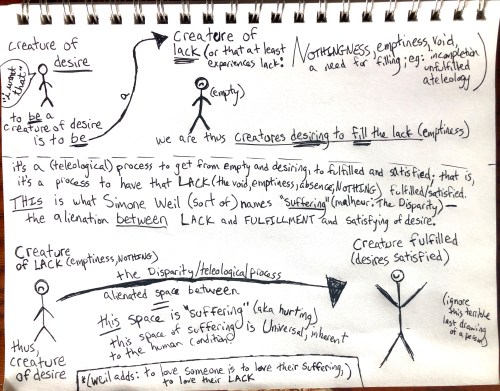

And this is where I really spun out. My mind went from things I’ve taught about teleology and that human condition of being incomplete, Freud’s death drive, Lacan’s elaboration on said death drive, and Simone Weil’s perspective on suffering through her concepts of affliction (or as she termed it in the French, malheur) and emptiness (or as she termed it in the Greek, kenosis).

What is consistent within all of these is the fact that while we individually experience different levels of being hurt and experiencing hurt, an inherent characteristic of the human condition is that we are all hurting.

Whatever hurting is (I’ll get to it, I promise), it is ontological. It is a universal dimension of what it is to be human. So you may not have been hurt the same way I have in my life, nor I you—paper-cuts, stubbed toes, heartbreak, death of a loved one, abuse, trauma, business merger falling through; the individual hurts can be different. Similarly, each of us may have various amounts of success, pleasures, securities, stuff. But one thing inherent to all of humanity is that we are ALL hurting.

If you have even just a rudimentary, passing knowledge of Sigmund Freud, then you’re aware that the joke is how obsessed the guy was with sex. In reality, his concept of the sex drive is simply that we’re driven by the pleasure principle, which is all about seeking pleasure and avoiding pain (undesired harm). But the problem was, he kept seeing examples in people where this isn’t the case. Freud noticed that people often repeat self-destructive behaviors, so he proposed another drive: the death drive—a kind of hidden force pushing us towards destruction and a return to a lifeless state. To Freud, the human condition is not only motived by a sex drive—seeking pleasure and avoiding pain. But also a death drive—we crave oblivion and a return to nothingness.

We desire the void.

We desire (a return to) nothing.

Jaques Lacan built upon Freud’s death drive and used it to explain his understanding of the human condition. Imagine back to when you’re a kid, and for the first time, you see yourself in a mirror. You recognize that the reflection is you, but it also makes you realize that you’re separate from everything else. This moment, which Lacan called the “mirror stage,” is when you start to form your sense of self. However, it also introduces a feeling of lack—an awareness that you’re not whole or complete.

Lacan believed that this sense of something missing sticks with us throughout our lives. This feeling of incompleteness drives our desires. We want things—money, love, success—because we think these things will fill that gap and make us whole. But no matter how much we get, that feeling of lack (the void, nothingness) never really goes away. Lacan had a fancy term for this elusive thing we’re always chasing but can never quite attain: the “objet petit a“. It’s a French term that translates to “little object a,” and it represents those things we desire that symbolize what we feel is missing. It’s not just any object but a stand-in for that fundamental sense of lack.

The “objet petit a” could be anything—a person, a job, a romance or relationship, a lifestyle—something we believe will complete us. But the trick is, even if we get what we think is our “objet petit a,” it won’t actually fill the void because it’s just a symbol of our deeper, underlying sense of incompleteness.

To Lacan, the ontological characteristic of the human condition is that void, that state of incompleteness, that nothing.

The one thing inherent to all of humanity is that we have nothing in common.

Or rather, the void and nothingness inside us is what we all have in common.

We are creatures of lack. And the death drive is our motivation to fill that lack.

I’ve taught about this indirectly when I discuss the concept of teleology, or purpose and function.

Because it’s not just about purpose and function, but about completion and fulfillment. Or rather, what I actually teach, is what I would call ateleology, a-teleology, the negation or contradiction to teleology. That is, that you will always be incomplete. And that’s kind of the point. The problems arise when we correlate brokenness and incompletion. Breaking can very well be part of the completion process, but when you come to understand that you will always be incomplete (or according to Lacan, lacking), then while you can break, you can never be truly broken—because to be broken is to first entail being completed.

That is to say, you can be hurt, but that isn’t the end of your story.

To be hurt is a part of the story, but it’s not the point of the story.

Well anyway, we’re all lacking. And we all desire to fill that lack and make it not be a lack anymore. But this isn’t where the “hurting” comes in. I don’t think hurting is simply because we are all lacking, that when I say that hurting is a universal characteristic of the human condition, that we are all hurting because of that void and nothingness. Because if that were the case, then all you would have to do if you did not want to exist as a being that is hurting, is trick yourself into believing you are something rather than nothing.

Or perhaps, you’d have to actively avoid facing yourself.

Which would be to actively avoid facing that lack. Believe that the objet petite a that you’ve latched on to is enough to make you a something. But all this does is make anything a threat and a danger that could remind you of that void and absence. You make villains outside, because you’ve vilified and demonized the you that is inside that you don’t want to face.

It becomes a competition.

But not one to win a prize. Instead it’s a competition to avoid having to face yourself. Or more to the point, to avoid facing your own lack. A lack that remains no matter what you try to fill it with.

No. Hurting isn’t equated to the lack. We don’t suffer because we lack, we suffer because we desire.

Alan Watts tells a story about the Buddha talking about this very concept.

“The Buddha said, “We suffer because we desire. If you can give up desire, you won’t suffer.” But he didn’t say that as the last word; he said that as the opening step of a dialogue. Because if you say that to someone, they’re going to come back after a while and say, “Yes, but I’m now desiring not to desire.” And so the Buddha will answer, “Well! At last! You’re beginning to understand the point!” Go away and try to stop desiring. But I can’t stop desiring NOT to desire. What am I to do about that? And the Buddha says, “Try then, to stop desiring NOT to desire.”

This is where things get interesting. Because I’m going to equate his concept and term “suffer” to hurting. (But I also want to make note of it as “hurt,” because I think this really draws it all together)

What is hurting? Hurting is suffering.

Why do we suffer? We suffer because we desire. But more than that, don’t we endure suffering for what we desire? The Greek concept for both passion and suffering are one and the same. Why? Because we willingly endure suffering for our passions. We willingly allow ourselves harm for the sake of what we desire.

Simone Weil elaborates on this notion, saying that we are creatures of desire. That is an inherent characteristic of the human condition. But why are we creatures of desire? Well because we are creatures of LACK. And it is in the process, the act of satisfying that desire that we all universally suffer. To experience desire is to experience LACK. And the disparity between that state of lacking and the state of satisfaction, THAT’S what Weil (sort of) names “suffering.” The space between…is suffering.

I ended up sketching this all out because I needed a visual. (I told you, I miss my whiteboard.)

You see, we are all of us (all of humanity) hurting, suffering. Why? Because we are all of us, creatures of LACK, and thus we are all of us, creatures of DESIRE.

We have nothing in common. We have nothing in common except nothingness, except that LACK.

And because of that lack, we have everything in common because we all desire.

We just differ on what those desires are, and what we believe to be the solution to satisfying and fulfilling it. And when we, when people, disagree on a subject, they tend not to just disagree on the subject, they disagree on what the disagreement is even about. There’s a lacking on different levels, and thus a suffering—a hurting, on different levels.

So why do hurting (suffering) people hurt (inflict undesired pain) on other hurting (suffering) people?

As I said earlier, “Because Fear!” is a valid answer and one I don’t disagree with. But again, I think there’s more to it.

Why do suffering people inflict undesired pain on other suffering people?

Because of…desire…?

Going back to what Alan Watts said. We suffer because we desire. We’re suffering(hurting)because we are creatures of desire, yes. But we also hurt (others) because we desire. We inflict unwanted pain because we desire. That isn’t to say that all examples of inflicted pain are because the individuals inflicting the pain actively and consciously (sadistically, you could say) desire to do so.

No. What I’m saying is that in our state of lack and our pursuit of filling that lack, in the disparity and space of suffering in between, we harm. We hurt.

Perhaps because we never learned how to actively seek out having our needs met in a healthy manner.

Perhaps because we were conditioned to believe the most important thing is to have our needs met, and damn anyone who gets in our way.

Perhaps we believe that if others experience inflicted pain, then it won’t make us feel so alone in the pain we’ve had inflicted on us.

Perhaps it’s because we’re under the belief that the satisfaction of our desires is only good and enjoyable if it means someone else doesn’t have their desires satisfied (this is what’s known as a zero sum game).

Perhaps it’s all a race (we do exist under capitalism, after all…).

Perhaps you never know.

Perhaps it’s a matter of a lack of communication.

Perhaps it’s intentional. But perhaps it’s accidental.

Perhaps you hurt people as a way to feel connected and not alone. Misery loves company and all that. And what if it is truly better what they say, that suffering alone in isolation is the worst kind of suffering?

“But the greatest suffering is being lonely, feeling unloved, having no one. I have come more and more to realize that it is being unwanted that is the worst disease that any human being can ever experience.”

– Mother Teresa

So yes, you hurt people because you’re afraid. But what are you afraid of?

Why do people hurt people? Because FEAR! Okay, but fear of what?

Is it fear of that LACK? (Even lack of connection?)

Or is it fear of never satisfying and fulfilling that lack? A fear that you’ll never get what you desire?

Maybe you’re afraid of those that threaten the idea that you have satisfied and fulfilled your lack, when in realty, you haven’t. And so you make villains of, and fear those, that remind you you are unfulfilled and lacking.

You see, I think self-preservation is a far more universal concept than sadism. And this is where the argument could be concluded that we hurt people (we inflict undesired pain) out of the fear that they have, or they are, or they will, hurt (inflict undesired pain) us. After all, isn’t one of the most primitive desires, the desire for safety? Thus, we hurt others who threaten our safety. And when we feel safe, we don’t feel afraid.

Safety = a lack of fear

We hurt others because we’re afraid of them that threaten our safety—our lack of fear.

We hurt others because of fear of fear. We’re afraid of feeling afraid.

What then, is that most primitive desire? To not feel fear.

But see, here’s where it gets tricky. William James, when talking about fear, said this (paraphrased):

“We don’t run from the vicious bear because we’re afraid of it, but rather, we are afraid of the vicious bear because we’re running.”

Our body responds how it instinctively and naturally responds to threats of potential or actual harm. Fear is secondary to this natural response of our body. That means we’re not avoiding pain because we are afraid, but rather that we are afraid because we’re avoiding pain.

So actually, while we hurt others who threaten our safety (the state of lacking in fear), it is because we desire safety.

We’re always lacking and never complete. We’re always incomplete. We’re never fully satisfied. Which means we’re never fully safe. And people have and are and will hurt us.

And we have and are and will hurt others.

We have and are and will hurt (inflict undesired pain) ourselves…

Point is, when I ask again, “what is that most primitive desire?” It isn’t to not feel fear, it’s to not feel undesired pain. Either way, the question of the most primitive desire? Is that for an absence. Sure, it’s an absence of something we’ve classified negatively (be it fear or pain), but it’s an absence regardless.

It is a desire for a LACK.

Creatures of LACK that desire…

LACK.

We are creatures of suffering because we are creatures of desire. We are creatures of desire because we are creatures of lack. As Alan Watts quoted the Buddha, if you can give up desire, you won’t suffer. But to give up desire is to somehow no longer be lacking. If we were creatures lacking nothing, then we would be creatures desiring nothing. And if we were creatures desiring nothing, then we would be creatures suffering nothing.

Did you catch that? Or do I need to repeat it, this time more slowly.

We are creatures that lack nothing. As such, we are creatures that desire nothing. Because of this, we are suffering nothing.

To desire a lack of suffering is to desire an absence. And in order to achieve this desired absence, you have to stop desiring. But you can only really stop desiring if you are no longer lacking. But the thing you desire is a lacking.

What I’m saying is…I am a creature of lack. That lack causes me to desire. That desire causes me suffering. Ultimately, what I would truly want is a lack of suffering. To attain that lack of suffering, I must stop desiring. To stop desiring, I must no longer be a creature of lack. However, I desire for an absence, a lack; which means I can never not be a creature of lack.

(Crazy? I was crazy once. They put me in a white room. The white room had rats! Rats? They make me Crazy!)

Well. If you find yourself confused, pinch, poke, or slap yourself really hard. Cause yourself pain enough that that’s all that takes your focus for a moment. Now you know why I really spun out thinking about all this.

So lets get back to the main issue, because I think now we have enough to give answer.

Why do people hurt people?

Why do suffering people inflict undesired pain (on themselves, and) on other suffering people?Because we’re all incomplete. We’re all lacking.

And we always will be.

It’s just this byproduct of our state of lack.

And we have no idea what to do with that.

Because when you have enough self-awareness to know you are lacking, why wouldn’t you lash out for not having your needs met? For not having your lacking filled? Why wouldn’t you get angry when political commentators capitalize on this feeling, and tell you its because all that fulfillment is going to someone else.

You LACK because others HAVE.

(lie)

The most clever lies are predicated on truth. Sure, there’s a lot of voices saying that you’re not lacking, or to just ignore it, or that it’s not true. But there’s even more voices that may not directly acknowledge or state that you’re lacking, but promise the solution. So we’re being sold on self-help guides, and promises of complete fulfillment. And maybe this is why religion is so successful. After all, what is religion if not the promise of fulfillment predicated on the human condition that you are lacking. They just disagree on what that genuine fulfillment is.

Or maybe we’re told to focus on the utter lack itself. The nothing. And rather than religion and fulfillment, we shift to nihilism. Embrace the void. Make it everything. (Nothing = Everything…)

And the bigger problem is, when we—when people disagree on a subject, they don’t just disagree on the subject, they disagree on what the disagreement is about. There’s a lacking then, on different levels, and thus a hurting on different levels.

So we focus too much or too little on the pain. Or we focus too much or too little on the suffering.

And I think that was the part of the discussion in that Philosophy Club meetup that kept nagging at me and I couldn’t let go of. It wasn’t that I needed an answer. It was the focus of the question and discussion itself.

PART 3:

WHAT DO YOU SEE WHEN YOU SEE HURT AND HURTING?

(or rather, WHERE IS YOUR ATTENTION?)

(or maybe, WHAT’S THE POINT?)

In her book, Gravity and Grace, Simone Weil writes, “I should not love my suffering because it is useful. I should love it because it is.”

She goes on to say, “We should seek neither to escape suffering nor to suffer less, but to remain untainted by suffering.”

I love the wording there. Shes doesn’t say we should remain unchanged by suffering.

But untainted.

I can’t shake the feeling though, that both of those quotes read heavily like something Tyler Durden would say in Fight Club. I wonder if he was well-versed in turn-of-the-century Christian Mystic, Marxist, Female Philosophers…

“It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.”

Did you know a caterpillar doesn’t just change, it basically breaks down completely and builds itself up as a butterfly? Inside a chrysalis, a caterpillar’s body digests itself from the inside out. The same juices it used to digest food as a larva it now uses to break down its own body. The fluid breaks down the old caterpillar body into cells called imaginal cells. Imaginal cells are undifferentiated cells, which means they can become any type of cell. These cells are then used to form the new body.

So caterpillars don’t change into butterflies. They’re broken down, destroyed completely (the Greek word for this is: apollumi), and then reformed.

“It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.”

I used to have a real problem with feeling grounded. With connecting to myself, and this physical existence. I looked into so many methods of centering and grounding. Meditation. Prayer. 12 Rules. Working out. Going for walks outside. Touching rocks. Smelling trees.

And I honestly tried them all. I wanted to take care of my body as well as my mind and my soul and my well-being. I realized when I began flossing again that I loved the pain it caused. Now I haven’t missed a day in five years. I would go for walks and focus on breathing and touching plants. I’d stop and smell trees. But I wasn’t present. I was simply trying to be. It wasn’t until I overexerted myself and my legs were in pain and I knew I had to keep going to get home was I grounded and present in that moment.

Through the pain.

For some reason, enough pain makes me forget even about myself. Or what I think is myself. With enough pain, I’m not concerned with masking and what I’ve come to believe I must be in order to connect in society; no I’m focused on the pain itself in that present moment.

That eternal now.

With enough pain, I’m not concerned with self-realization, or self-actualization, or manifesting my authentic self, I’m not concerned with who I truly am, or who I ought to be; no I’m focused on the pain itself in that present moment.

That eternal now.

See, I’m not saying it’s wrong to engage in and perform centering practices. Nor am I advocating for masochism, sadism, or even religious practices of self-harm.

My point is that I’ve realized what was nagging at me and what I couldn’t let go of since that Philosophy Club meetup. And it’s the question, “What does pain do?”

What do you see when you see someone in pain, and suffering?

What do you do when you yourself are in pain, and suffering?

Now this doesn’t quite translate as a one to one correspondence, but I think the point remains. That as is the case with all things, it’s always a matter of perspective. No. Not perspective. It’s a matter of focus. It’s not to ignore the pain and suffering in the world. Go to your cave, your happy place.

But IF that pain and suffering is not just to be an inevitability, rather it is a defining characteristic of the human condition, then what are you to focus on?

(Think about that activity of holding one finger on one hand closer to your face and another finger on the other hand further away from your face and what happens when you focus on either. The fingers don’t disappear, but with one thing being the focus, it’s clearer and the other—while present—is blurry, distorted. Same thing with photographs. What the focus is on changes the photo while not cutting out the other aspects of the photo.)

I’ve been hurt (that is, experienced undesired pain). A lot.

And I’ve written about it. A lot.

I’ve also suffered a lot. And I think that after concluding Part 2 of this, the point is that my suffering isn’t something unique to me, but ontologically part of what it means to be human.

For most of my life I’ve had a kind of obsession with the concept of death, engaging in my own unique study of thanatology. I used to say that death was my muse, when I was being brooding and artsy (it wasn’t a phase, mom!).

What I’ve found is that when you’re as open about your pain and suffering, others feel the ability to be just as open about theirs (as if they never were before…). When you live openly about going through Hell, you begin to discover and connect with others there. In their song, “Evangelists,” (link) by Gang of Youths, there’s a lyric stating “I have made more friends in Hell than I’ve made in Jesusland.”

Misery does love company.

But it doesn’t have to be with the exclusive purpose of focusing solely on the misery itself.

It isn’t about wallowing in that misery or nothingness constantly. It’s about recognizing that state as part of being, and using it to connect with others.

Eastern Orthodox theologian, Lazar Puhalo: “Suffering draws forth empathy from people. And empathy is what causes us to rise above evil. We’re the MOST human when we respond to someone else’s suffering. When we open ourselves to other human suffering. We’re halfway to heaven when we have eyes to someone’s suffering.”

Empathy fuels connection. Because it’s feeling with people. But what exactly are you feeling with them?

If we’re to add these concepts up, based on what both Lazar Puhalo and Brené Brown are saying, then:

(I told you, I REALLY miss my whiteboard…)

Suffering leads to empathy and empathy leads to connection.

I may not be able to empathize with you with regards to the specific pain(s) you’ve endured in your life, but I can empathize with your suffering. Your nothingness and lack. Because that state of lacking and that state of suffering is universal. But only if you choose to open up and face it yourself, and in turn, share it.

Which means you have to face it yourself. After all, the saying goes that people can only meet you as deeply as they’ve met themselves.

People can only meet you as deeply as they’ve met themselves.

But what if we do?

Where do we do it? Where can we do it? When? Is it only when something happens that is painful? Is it only when someone shares?

“It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.”

We are all in a state of suffering because we are in a state of lacking. We’re suffering because we’re incomplete and suffer in our process of striving for completion.

We all have already lost everything, because we never had anything to lose in the first place. To be lacking is to be free to do anything.

What does bring us together? What’s a universal unifier?

NOTHING.

You see, the problem I have with that Fight Club clip isn’t what Tyler Durden is saying, it’s that generally it is taken from this individualistic, self-centered perspective. But what about if it’s taken in the collective sense?

A community is a group of like-minded individuals with gathering over shared characteristics, or things in common.

Finding community is becoming increasingly more difficult in an age where the emphasis is on what separates us, a desire to be unique, and more and more niche labels to form very specific and thus not very populated, groups.

When I first moved down to Colorado Springs, my wife (at the time) and I began looking for a church to attend and get plugged into that particular type of community. A couple of the major aspects we were looking for were how the church felt about women, and how inclusive or affirming they were about the LGBTQ community (boy did that come into play later…).

And yet the thing that rubbed me the wrong way about a couple of churches that nevertheless met our requirements was how they treated the liturgy of Communion. I remember the distinctly negative feeling I got when a church introduced the elements of Communion, but made a point of emphasizing that you were only allowed to partake if you were a Christian believer. Anyone could come to the communion table, but not everyone. I remember thinking, “Why make a point of emphasizing that? Who comes to a church and engages in Communion, or any aspect of the liturgy, if they don’t believe? And if they do, what’s the matter with it? What does it impact anyone else? Why emphasize an exclusion that you made up?”

As I’ve grown more and learned more about my beliefs, I realize how any sort of hierarchy of human value and worth has always rubbed me the wrong way. Exclusion is inherently othering, which is inherently saying some have more value than others—those some being the ones that are like-minded and individuals that are part of your community. You may be extending an invitation to the others, the outsiders and saying they’re welcome to join your community, but treating them as outsiders and others in the first place is engaging in exclusivity and inherently saying there is a hierarchy of human value (even if you try to say they can have the same value once they complete certain tasks and become a part of your group, rather than apart from it).

I’ve realized that there’s something about the liturgy of Communion to me that is inherently anarchistic.

Communion is the act of banqueting (specifically bread and wine) around the remembrance of the death of G-d. It’s a shared meal with people you have nothing in common with.

Catch that? It’s a shared meal with people who universally share in common one thing: Nothingness.

LACK.

There is no hierarchy in Nothingness…

Communion is the gathering together of creatures of lack, embracing and ingesting the LACK. After all, the notion of the death of G-d is, philosophically, the ultimate lack. The notion of G-d, philosophically, tends to be the name or label we put on that which ultimately provides meaning. And in religion, the notion of G-d tends to be the name or label that is placed on the…fulfillment that human beings are in lack of. It is what’s supposed to make you whole, complete, NOT a creature of lack anymore. Communion, then, is about embracing the nothing, embracing the lack, and ingesting the lack (the sacraments are to symbolize Jesus’ body and blood, Jesus being G-d). Everything about Communion and about the death of meaning and fulfillment. It is about the ultimate lack: the nothingness at the heart of everything, including the absolute. It’s about embracing the lack, and ingesting the lack into yourself.

But doing so together. Collectively.

What we have can separate us. Divide us. But what we don’t have, our singular lack, unifies us.

We suffer because we lack. We suffer because we’re incomplete and never will be complete. But being creatures of lack, thus creatures of desire, and thus creatures of suffering, doesn’t have to separate and isolate us. It can very well be the thing to unify use and bring us together.

Shared suffering is far better than suffering in isolation (trust me).

To quote Mother Teresa again, “But the greatest suffering is being lonely, feeling unloved, having no one. I have come more and more to realize that it is being unwanted that is the worst disease that any human being can ever experience.”

Unless you realize that we are all creatures of suffering because we are all creatures of desire. And we are all creatures of desire because we are all creatures of lack. We are all incomplete.

And maybe it’s not about finding completion together (as if we’re all incomplete that come together to complete like pieces of some universal puzzle). Maybe it’s just about being incomplete; together.

How do we strive to NOT hurt each other?

That’s a tricky question. But perhaps instead of hoping to do so by filling the lack, we embrace the lack.

Together.

There is an inherent lack of hierarchy in Nothing…no one has any greater or less value in nothingness.

Maybe the banquet table—specifically the communion table—is the solution. Not as a means of ignoring the lack, or ignoring the suffering, but making it the main focus.

And perhaps in doing THAT, we stop hurting each other and ourselves. At least for a little while. It may not solve the problem of pain and suffering, and we may very well go back to hurting each other. But maybe the more times we have where we connect with our own lacking, and our own suffering, and then share that with others, we’re too occupied to cause pain.

As each of us—our hands full of bread and wine, focused not only on our own nothingness, incompleteness, and suffering, but in looking around the table—recognize that we’re not alone; witnessing and connecting to others with hands full of bread and wine, focused on the very same nothingness, incompleteness, and suffering of themselves.

The most transformative discussions occur around a banquet table because people have to put their weapons down to eat and drink.

How do we strive to NOT hurt each other?

I don’t know. But maybe you and I can grab some bread and wine and talk about it and figure it out together.

->and the world will be better for this…

Please consider supporting me and my family on Patreon by clicking this link.

Thanks to all my (present and potential future) patrons, parishioners, and anonymous supporters for their encouragement and support in writing and publishing this piece:

Abel

Astrid

Caleb

David

Gabe

Jess

Jen

Kelly

Manis

Mathunna

Max

Trini

Pingback: Heaven Is Hell (And That’s A Good Thing) | Leaving La Mancha